The most impressive sex lecture I ever had in my life was from my Maverick grandmother. As you'll see, she didn't moralize. She just wanted some good manners.

I was getting fresh with a girl on Grandma's porch. It was during high school days.

"Maury, Jr.," she said. "you quit that."

"Oh, Grandma, you used to do the same thing back in Virginia behind shutters."

Pow! I got it in the kisser in front of everybody.

"What do you think shutters are for, you young fool?" Grandma asked.

* * *

Grandma never let me forget our ancestors back in Virginia. They included an overabundance of Episcopal preachers, army and navy officers, the most important military person being Commodore Matthew Fontaine Maury, the oceanographer, who lived out his last days as commandant of cadets at Virginia Military Institute.

Then she would say: "You come from French Protestants. Your people were run out of France by the Roman Catholic Church."

"But, Grandma, that happened more than three hundred years ago."

"I don't care," Grandma would always reply, "it was terrible what those Catholics did."

Well, when she was in her upper nineties, she began to talk about death. One day while in bed she brought the subject of death up with the comment, "Maury, Jr., I don't have much time left. I think you should get a priest to talk with me."

"Grandma, do you want a Roman Catholic priest or an Episcopal priest?"

Total silence. Her eyes were completely closed.

Had Grandma died of a heart attack?

Suddenly, both eyes opened, saucer big. She propped herself up on her elbows. Pow! I got it in the kisser.

I went to the door, turned around, and waved at my grandmother. She shook her fist.

* * * Grandma was the cop in the family. She had to be because on those Sunday reunions we Mavericks would go after one another like Kilkenny cats. Those were the great cats of Ireland that fought one another so hard there was nothing left but their tails.

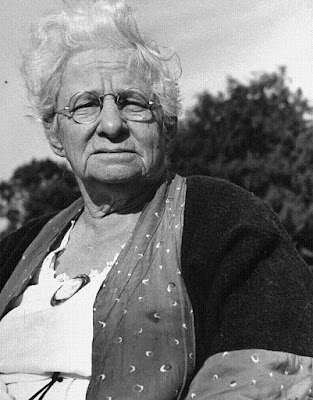

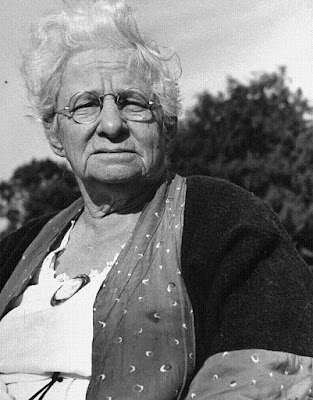

She was self-educated, a victim of the Civil War. There were no schools when Grandma was growing up. Her older sister, Ellen, later a society columnist, was formally educated, dated Woodrow Wilson and decided he was a stuffed shirt. But Grandma never saw the inside of a school. She never bragged on the Civil War as if it had been a good thing, and I was always proud of the fact that she used to tell me: "President Abraham Lincoln was a decent man."

A beautiful young woman when young, she had eleven children, the youngest of which was my father, whose real name at birth was Fontaine Maury Maverick. Although my father dropped his first name when in high school, Virginians insist on using it, and so when I go back to Charlottesville, the old-timers will say, "This is Fontaine's boy."

By the time I grew up, Grandma, worn out with so many children, looked a little like Benito Mussolini, and on occasion acted like him a lot to keep the family discipline. She remains one of the most powerful influences in my life.

On the tombstone for my grandparents it reads: "They lived together for seventy-two years and made many people happy..." Brothers and sisters, she was the cat's meow.

September 14, 1980

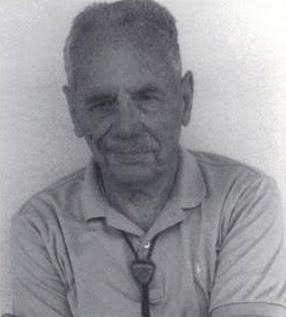

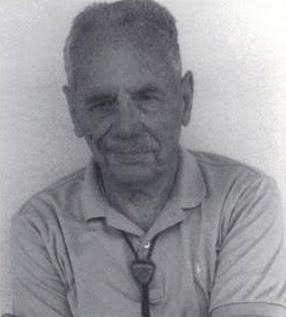

Papa MaverickA tempestuous man, my father couldn't open the ice box without getting into a fight with the milk bottle, or so I thought sometimes. He could be heavy medicine, and I had to get away from him now and then, but I knew he was something out of the ordinary. The inscription to him by Carl Sandburg sticks in my mind: "For Maury Maverick—fighter, freedman, fool, poet, zealot of freedom. . . ."

I am well aware of the fact that my father had about as many enemies in this town as friends. One time as a child, when I was worried about him, I went to see my cousin Reagan Houston.

"Maury, Jr.," said Cousin Reagan, "your father is the only politician I have ever known who will deliberately cross the street to start a fight with someone who is minding his own business. He loves this city as few people do, but he feels compelled to fight half the town. Whatever his faults, he is not a person who indulges in self-pity. Maury can take it and so should you. Now get the hell out of my office."

My father was the youngest of eleven children. Grandma Maverick told me: "The day your father was born, he just walked out wearing a diaper, a stovepipe hat, and with his fists up ready to protect himself from the teasing of his ten older brothers and sisters." That may be how he got his combative personality.

* * *

When I was a child, we would play the alphabet game together on Sundays. Starting with the letter "A" he would tell me to think of places we could visit. "A" for Alamo, what else? Off to the Alamo we would go. At the Alamo he would tell me: "Our Anglo ancestors were brave people fighting for liberty, but they also tried to maintain the system of slavery. Get all sides of history and figure out the truth. If you have any sense, it will make you love our country more intelligently."

My old daddy was mayor of San Antonio from 1936 to 1938 and was the first mayor in these parts to bring doctors to the City Health Department who were board-certified public health specialists.

The doctors told him, and so did the policemen who had common sense, to let the prostitutes operate in a specific location, have health clinics to help prevent venereal disease, provide police patrols to keep young men from getting their throats slit, and let the military set up their own clinics for its soldiers.

That was done until the preachers stopped it. The prostitutes scattered all over the town, disease went up, crime generally increased and so did rape.

* * *

[My father designed] a cross during the worst of the Depression following the last days of Herbert Hoover as president. My father had set up a cooperative camp, but let him tell the story as quoted from his autobiography:

I had organized a colony. The Bonus Army got run out of Washington and some had come to San Antonio. The contingent of veterans and their families camped at the San Antonio Fairgrounds and were starving and sick.

I made arrangements with the railroad company to get free freight cars to be used for houses. We had a population of 250-300. Here in the new colony some men, or a whole family, would come into camp and ask for something to eat and a place to stay. Quite often they would be alive with lice and weak with fever and disease. I made a deal with doctors to deliver babies at $10 each. . . . We put kids in school. . . [Maury, Sr., disliked much about the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church but, as a symbolist, collected Christian crosses, which he regarded as clenched fists.] With friend, Charles Simmang, an engraver, they designed a symbol in the shape of the cross. . . . At the top of the cross there was a representation of the world showing the continents of North and South America, expressing the hope that we might have peace. In the middle there was the Alamo, a symbol of sacrifice. There was a cap of liberty, and also a wheel of industry, and a plowshare, on the basis of equality.

If you look at the cross, you will also see the working tools at the bottom—the dignity of labor—and above that a clenched fist—the right of protest. The lone star stands for independence, and in back of the cross there is a glory.

I am of the opinion my father was a deeply religious person, although I am not sure what the much-abused word "religious" means—it is almost embarrassing to use the term. But I do know with certainty—no "think" here—that he had a general suspicion of organized religion and of "men of cloth." He would tell me that one of the reasons this is a great country is because under our Constitution you could tell a preacher to go to hell.

Here are some of the things he would say about religion when I was a little boy, things I didn't hear at St. Mark's Episcopal Church: "Maury, Jr., let me tell you about Jesus. He was a loudmouth brave little jew, a rabbi who put the pants on the stuffed-shirt Romans and stuffed-shirt Jews. If he came back to earth he would get run out of every church and synagogue in town. You know what we people in the New Testament were around the time of the crucifixion? In terms of political reform we were the CIO Jews, and the ones who held to the Old Testament were the American Federation of Labor Jews. The AFL Jews were the establishment Jews. We were the radical Jews. Since then things have sometimes become reversed. Too often we Christians are the reactionaries. We have needlessly hurt people, and we have shunted aside the radicalism of Jesus.

My father collected [other] crosses and crucifixes, mostly Catholic, by going to Mexico on trips specifically to find them. He did the same thing in Ireland. But his favorite cross was a simple wood one made out of the original timbers of the Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, and over which Patrick Henry uttered the spine-tingling words: "Give me liberty, or give me death!" He asked for that simple cross when he went into the hospital to die.

"You remember this, Maury, Jr.," he told me from under an oxygen tent. "Part of the cross must always be a clenched fist against economic and social injustice."

After he died, the nurses packed everything but the cross next to his bed. There it was by itself, the old rugged cross. . . .

* * *

During his last eight years of his life, Maury, Sr., never touched a drop of alcohol, but he had his share in his younger days.

One time he told me, laughing as he said it, for he loved Roman Catholic Archbishop Robert Lucey: "Maury, Jr., I saw you drinking one of those sissy cocktails at that party last night. You are a disgrace to the Maverick family. Son, don't you know the only way to drink is to drink a pint of whiskey as quick as you can and get in a fistfight over the Catholic Church?"

* * *

As I remember it, my father especially gravitated to three clergymen: Rabbi Ephraim Frisch of Temple Beth El, Jesuit Father Carmen Tranchese of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Archbishop Robert Lucey, who told me one time: "Maury and I got into a lot of trouble together. When I'd open my mouth your father would stick his foot in it."

When my father did participate in organized religion, it sometimes would turn out to be a disaster. The worst was one day across from Travis Park at St. Mark's Episcopal Church. After services were over and while he was shaking hands with the preacher, one of San Antonio's most important "high society" women came up and in a loud voice accosted him with the comment: "Why, Maury Maverick, what are you doing in church? I've heard talk around town that you were a communist, but I guess you couldn't be if you go to the Episcopal Church."

Poor old Papa's face went livid. With the voice that would have been the envy of a drill sergeant, he said back to the woman: "I hear talk around town that you are an old whore, but I guess you couldn't be if you go to the Episcopal Church." Episcopalians began to scatter like chickens, the preacher rolled his eyes in back of his head, and I damn near wet my pants. God Almighty, that was a nightmare.

Speaking of nightmares, my old man was criminally indicted one time for purportedly conspiring to pay poll taxes. In the old days, thousands of Mexican-Americans were in effect disenfranchised through the poll tax. The jury came back with a unanimous verdict of not guilty. His lead lawyer, Carl Wright Johnson, was a magnificent trial attorney. If you want a lesson in life, try standing by our father waiting for a jury to come in and tell you it might send him to the pen.

* * *

Then there was an episode noted by Don Carleton in his book

Red Scare!, when Maury, Sr., agreed to let Emma Tenayuca, then a communist and labor organizer, and some of her colleagues to speak at the Memorial Auditorium. Carelton wrote: "The Communist Party in Texas decided to hold its 1939 state convention in San Antonio and applied for a permit to meet in the Municipal Auditorium.

Mayor Maury Maverick's decision to grant the permit unleashed a whirlwind of protest in the city from the Catholic leaders, American Legion spokesman, the Ku Klux Klan and others. [The] city auditorium was surrounded by a hostile mob of an estimated five thousand people. The mob descended on the building, heaving bricks and swinging clubs. The police estimated that seventy-five percent of the rioters were between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five."

I saw my father's career come to an end [that] night when, as mayor, he [did indeed] let a handful of communists and sympathizers gather at the Municipal Auditorium. For days every newspaper in town whipped up the idea of hatred. [The night of the riot] my entire family hid out at the home of John Wood to keep from being murdered. Parts of the mob came to our home looking for us; others went out to intimidate my grandparents.

My father understood the mob, made up mostly of blue-eyes like he was, but he never got over the mob being led by a Jew, a Catholic priest, and a Lebanese-American. "Those are all three minorities who have suffered and ought to be the first to stand up for free speech," he said. Life was never the same for him or anyone in our immediate family after that riot. Even today that is true. Have you ever had a mob trying to find you to kill you?

My old man knew he had rung the bell pretty good with the help of his wife, Terrell: He was the only congressman from the South to vote for the Anti-Lynching Law, co-author (inspired by Dr. Dudley Jackson) in establishing the National Cancer Institute, one of the prime movers in beautifying the San Antonio River and La Villita, and the first mayor to bring modern municipal government to San Antonio.

The last time I saw him on the streets of San Antonio was in the morning at La Villita, where he would go several times a week to see if the place was being cleaned up from before.

"I'm washed up in San Antonio politics, but I'm still the mayor of La Villita," he would tell me now and then, as he did that day.

[But while still mayor, Maury, Sr. continued the battle. There is the story that began:] "Mayor Maverick, this is Elizabeth Graham calling you from the Conservation Society, and I want you to know that we are not going to permit you to put flush toilets in the Governor's Palace."

"Why not?" my father asked.

"Because it would not be authentic. They did not have flush toilets in the days of the Spanish governors."

"Yes, that's right, Elizabeth, and in the days of the Spanish governors they didn't have children of tourists urinating in the back patio. It smells bad, and the health department says I have to do something."

"Maury, we grew up together as children and I'm telling you there will be no flush toilets."

A few days later house painters began to put up scaffolding in front of the Governor's Palace. Elizabeth Graham, Floy Fontaine, and all the dear ladies wanted to know what was going on.

"The mayor told me," said Juan Rodriguez, the foreman of the job, "to paint the Governor's Palace red if you don't let me put in flush toilets."

Wanda Ford, Graham's daughter and my first cousin, tells a different version, but I have just told you, so help me God, how flush toilets came to the Governor's Palace.

* * *

During World War I Maury, Sr., served as first lieutenant, Twenty-eighth Infantry, First Division, where he won the Silver Star for gallantry, captured twenty-six German soldiers single-handedly, and was severely wounded in the shoulder.

Judith Doyle, one of his biographers, wrote: "On November 16 (1934) the nurses at the (Mayo Brothers) clinic wheeled (Lieutenant Maury Maverick, Sr., U.S. Army retired and congressman-elect) into the operating room, where he remained under anesthesia for over five hours. The surgeons removed the large tumor (caused by shrapnel) and sawed off the backs of five of his vertebrae from his skull to his shoulders."

At one point someone rushed out of the operating room and warned the anxiously waiting Terrell to prepare for the worst. But Maverick pulled through, and the nurses rewarded him with a medal of St. Jude, the saint of impossible causes. By New Year's Day, he was stumbling along a chilly Washington alley, leaning on Lyndon Johnson's arm. Two days later he stood on the floor of the House and took his oath (as U.S. Representative from Bexar County).

My father was horribly wounded from World War I combat and remained partially cripple to his death. My first memory was to hear him cry out in pain at night. My mother would fill the tub with hot water, and I'd go sit with my dad. We had big talks about war, and he would tell me: "You must never be for war. Never."

He took all his medals and pasted them to a death's head as a protest against war.

But then, years later, Hitler began to move.

We would listen at night over the transatlantic radio to Ed Murrow, who had the spine tingling sign-on, "London Calling!" One night there had been an especially cruel bombing of London. You could hear the fires burning and the screams of Englishmen. My father's back was turned to me. It was hot and the sweat was running down those crevices in the body where the German shells had ripped away his flesh and bone.

Murrow signed off.

Slowly my father turned around, and for the first time in my life I saw him crying. Great tears were rolling down his face. "Maury, Jr.," he said, "we have to go to war. We have to kill that son of a bitch Hitler."

But even his combat wounds got Maury, Sr., into trouble, as he explained in his autobiography,

A Maverick American, which Heywood Broun thought as good as Erich Remarque's

All Quiet on the Western Front regarding the chapters about war.

On a hospital ship going home, a chaplain held a prayer meeting and proclaimed that the German soldiers were such cowards that they had to be chained to their machine guns.

"If they were cowards," interrupted Lieutenant Maverick, "then it didn't take any courage for us to whip them. What do you know about combat?" He called the chaplain words that [

Express-News publisher] Charlie Kilpatrick, a southern gentleman, will not let me repeat in this family newspaper.

Lieutenant Maverick, twenty-two years old and a former cadet at Virginia Military Institute, was placed under arrest. A wireless was sent to New York to have him investigated for possible court-martial. Upon the ship's docking, an investigation was conducted, but nothing came of it.

In World War I, reserve officers were retired in rank for serious injuries. So, until the day he died, my father was "Lieutenant Maverick."

My father also hated to have a voter come up to him and say: "I bet you don't know my name." He equally hated having people slap him hard on the back because he had been brutally wounded there in World War I.

Anyway, we were out pressing the flesh one election time in a German-American community in Bexar County. A big, beefy guy came up and hit my father on the back and knocked him down. While he was down, the man yelled at him in front of many people: "I bet you don't know my name."

Papa got up, swung from the ground, and knocked out the beloved voter, and then shouted, "No, you German son of a bitch—I don't know your goddamn name, and I don't want to know your name."

We lost that box three hundred to one, but it was a moment to cherish.

* * *

I have the obituaries about my father from the major newspapers of America and even some from London and Paris, but what might be a real treat is to quote from World War I combat letters he wrote to his father, Albert.

I never saw the letters myself until about a year ago when my cousin, Jane Welsh Reyes, gave them to me. I have given the letters to the Barker Historical Center at the University of Texas-Austin.

Without further ado here are excerpts from some of those war letters, all written in 1918 and 1919:

"Dear Papa: The First Division always gets the real fighting. The First never fights except to win a battle. When we travel we are placed from point to point on weak spots of where offenses are contemplated."

"Dear Papa: A score and three ago, my forefathers brought forth upon the great continent of America a lad none other than myself, born in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal."

"And now, as the world is in the throes of gripping battles, he, the lad born in the very shadows of that immaculate building, the Alamo, finds himself in France in order that those who have no conscience (the Germans have none) may die, and those who have may live."

"To tell the truth, Papa, I really should not let you know, but I have been wounded. Tell no one!"

"For suppose, Papa, that you should say so and a spy should hear it (and spies are everywhere). The spy would tip the imperial government of Germany off, and the Germans would then be unafraid, and would probably advance instead of retreating."

"Papa, be careful.

Must democracy die? I say no, it shall not.

Keep Quiet. No great victory was ever built upon unbridled license of foolish talk."

"Dear Papa: The Germans claim 'Gott Mit Uns' (God is with us), but we Americans have got mittens which keep our hands as warm as Germans. George (his brother) came to see me (in the hospital). I have some grapes, chocolate, dried fruit, chewing gum, and tobacco."

"When I came here I could not move; now I can get out of my bed and stay on my feet a few seconds. When I came I looked out the window and all was green and beautiful, but now the leaves are yellow and falling to the ground."

"I am some sixty miles from the front, but starting on the minute with my birthday (October 23) the heavy guns talked. Well, I am tired and I guess I will lay my head down. Love."

"Dear Papa: Not too many moons will pass and Maverick in a flashy suit will get in a palatial taxi and say, 'Home, James.' I will see a major general in the path of my motor and I will say, 'James, run over the general.' Then I will see an 'old buck private' and I will say, 'Enter my limousine and ride.' I shall know no rank, I shall curse my enemies and love my friends. Again I will be human."

"Well, Jerry [the Germans] has given in. I cannot describe it, and if I should tell you all I saw, you would think me sentimental. But suffice to say every Frenchman and Frenchwoman was out on the streets."

"The veterans of 1870, with rather oldish voices, collected on the streets. In one bunch, some twenty or thirty, some with guitars, sang 'Madalone,' a happy, jolly song."

"Then the old Frenchmen stopped. They sang the 'Marseillaise' . . . the Frenchmen stopped laughing; they took off their hats and cried."

"That night (in Paris) the Frenchmen swelled into the thousands. A band began playing the 'Marseillaise' again. Of course, the Frenchmen all started crying again. Then the band played 'The Star-Spangled Banner' but there was no singing for we Americans don't know the words. But it meant more to us than ever before. I know where my thoughts were—to America, to Bexar County, Sunshine Ranch on Babcock Road and home."

"Dear Mr. Maverick: The Red Cross wishes to notify you of the return to this country of First Lieutenant Maury Maverick, Twenty-ninth Infantry, Company M., who landed at Staten Island, New York, December 28, 1919."

"Dear Papa: At the Lambs, 130 West 44th Street, New York. This club is composed of the most brilliant actors in the world along with playwrights. I have met Arbuckle, world-famous comedian. He was born on the Cibolo Creek, eighteen miles from San Antonio. I have also met Gene Buck, playwright for the follies, John Barrymore, John J. McGraw and other men equally famous. . . ."

In his autobiography,

A Maverick American, my father wrote of going "over the top" and of the time he was wounded. . . . I leave you with a few excerpts from those chapters:

"Into the Argonne we marched. Frank Felbel, a little Jew, was commander of my company. He was shy. He spoke of art and the opera. 'Maverick,' said Felbel, interjecting like a professor, 'did you ever read Le Bon's

Psychology of War?'"

". . . great shrieking noise came, then a dull explosion. Gas! Gas! Soon we marched on. We were getting lost. I stumbled. It was the body of a dead man, and he was soft and rotting and slippery. . . . It was near the village of Exermont."

"We started to advance again. A shell burst over my head. It tore away part of my shoulder blade and collarbone and knocked me down. I looked at my four runners, and I saw that the two in the middle had been cut down to a horrid pile of red guts and blood and meat. Felbel was dead, and there was no officer to take my place. I got up and reformed the lines again."

"But I was losing so much blood. I finally got to a field hospital. I passed out. But when I did wake the Germans were shelling. I was in the ward for severe cases. There were ten of us, three Germans and seven Americans. A German close to me had most of his face shot out. From him I first learned of pensions and social insurance. He said they came from German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. . . ."

* * *

I hesitate to describe the deathbed scene because my old friend, Herschel Bernard, claims that my father never would have had time to die if all the death scene stories I tell really happened.

But this is a true story, a story Willie Morris made famous in his book

North Toward Home, and one LBJ loved to tell.

My father looked like death that last day of his life as I sat by him trying to make small talk. Finally, I couldn't take it any longer and started to walk out of the hospital room to regain my composure.

"Maury, Jr.," he called out just as I made it to the door, "come back here. I want to give you a compliment."

"What is it, Papa?"

"Son, I want you to know you didn't turn out to be as big a horse's ass as Elliot Roosevelt."

"Oh, Papa!" I said. We embraced and both started laughing. Thirty minutes later my father was dead.

* * *

Some years later, Johnson got mad at me 'cause I was defending war resisters. He had one of his aides call me up and tell me my father was wrong. Johnson said I was a horse's ass. I'll never forget that.

The Sweet and Sour of Ancestors

I am up a creek without a paddle about doing this particular column on a book entitled Turn Your Eyes Toward Texas by Paula Mitchell Marks

By the time I get through with my writing for this Sunday, my cousin, Ellen Dickson, who wanted me to review the book, may wish she had left me alone.

I had decided to refuse to do a review of the book because I first thought Turn Your Eyes Toward Texas would be a bootlicking good old Texas family book, but the truth is that although it is generally favorable to my ancestors, it also rawhides Sam Maverick on occasion.

For example, the author quotes one J. David Stern in William Safire's book, The New Language of American Politics, as saying: "Old man Maverick, Texas cattleman of the 1840s, refused to brand his cattle, because it was cruelty to animals. His neighbors said he was a hypocrite, liar, and thief because Maverick's policy allowed him to claim all unbranded cattle on the range. Lawsuits were followed by bloody battles and brought a new word to our language."

I question that statement. At least the family version is that he knew almost nothing about cattle, that he had been paid a debt in cattle, did not brand them and let them run at will. None of my aunts and uncles and cousins, including the ones who would take a drink — tell the truth and shame the devil — ever mentioned cattle.

The word "maverick" got around the world, by the way, through the cattle boats that went to the distant corners of the globe. Rudyard Kipling used the word in his poetry.

What Sam Maverick did do that concerns me is that he was at one time the biggest land speculator in the Republic of Texas and later the United States. "Only the czar of Russia owns more land," was the common expression in San Antonio.

One must take the sweet and sour of his or her ancestors. Turn Your Eyes Toward Texas relates: "It was not easy to look down on the many cultured Mexicans living in San Antonio, but Anglo-American newcomers often managed to do so. To Maverick's credit he was to speak out against such prejudice." That's the sweet part. The sour part: My great-grandparents brought the first black slaves to San Antonio after the fall of the Alamo.

Sam and Mary came with their slaves from Alabama. As their party made Cibolo Creek east of San Antonio, Indians threatened attack. The black slaves, a man named Griffin in particular, saved the day.

A few years ago, when we Maverick's celebrated 150 years in San Antonio, an Episcopal priest at St. Mark's asked us to give thanks.

I gave thanks to those black people, and, as I looked around the church and saw some three hundred relatives, all descendants of Sam and Mary Maverick, it dawned on me that it was at least arguably proper to say that none of us would have been sitting there if it had not been for the bravery of the slaves.

I wonder sometimes if there are descendants of those slaves in San Antonio. I would like to thank them. And apologize.

Sam's wife was a Tuscaloosa, Alabama, girl, six feet tall and eighteen years of age when she married her thirty-three-year-old husband. Formally educated, she was one of the few Anglo women, if not the only one, in the San Antonio of 1838 who could fully read and write English. Her diary of early San Antonio is considered a treasure by historians.

Time and time again she was threatened with death through warfare with the Indians in and around San Antonio. As an old ACLU lawyer, I have guilt feelings about the way the Indians were treated, but during those moments when she faced death, I rather think my great-grandmother would have told me to go to h--- if I had been alive and mentioned the ACLU.

Sam and Mary's children began to marry. According to Turn Your Eyes Toward Texas, "The younger Sam Maverick married Sally Frost in 1872. That same year George married Mary Elizabeth Vance of Castroville, and in 1873, Willie married Emily Virginia Chilton. The only surviving daughter, Mary Brown, would wed in August of 1874, selecting future ambassador to Belgium, Edwin H. Terrell, and youngest Maverick sibling, Albert, would marry in 1877, taking as his bride Jane Lewis Maury."

All those Maverick children in turn had more children than you can shake a stick at. My grandparents, Albert and Jane Lewis, had eleven, the youngest of which was my father, Maury. You would have thought those Mavericks were Roman Catholics, they had so many children, but in truth they were passionate Episcopalians.

Warts and all, Sam Maverick had a pretty good throw of the dice. I think about that when I sit by his grave, in the cemetery on East Commerce. I go there fairly often.

In 1835 while living in San Antonio he was a scout for [Texas revolutionist] Ben Milam, who died in his arms from combat. Before the battle started [Mexican] General Martín Perfecto de Cos nearly executed Sam, but a local Mexican intervened and saved his life.

The next year he was elected by the defenders of the Alamo to be one of their delegates to Washington-on-the-Brazos and there signed the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Texas. He was, in 1839, the third American mayor of San Antonio and later its senator to the Republic of Texas.

Taken prisoner by a Mexican army in 1842 and marched to Perote prison, halfway between Mexico City and Veracruz, Sam was placed in chains. [When Mexican authorities released Samuel, they gave him those shackles, which are now at the University of Texas at Austin.]

Those chains haunt me. Time and time again when I was a little boy my father, sometimes full of bootleg whiskey, would give me the treatment about them. We would act as if we were in the U.S House of Representatives, this is Grandpa's barn, the chickens roosting on the rafters and with Beck, the mule, acting as the speaker.

"Will the gentlemen yield for an observation on liberty?" Papa would thunder. Then, God Almighty, what a lecture I'd get on the Bill of Rights and Jefferson's need now and then for revolution.

June 18, 1989

Early Rebel Relatives - Sons of Liberty Inspire Patriotism

On March 5, 1770, the first five men who gave their lives for this country were killed in what has come to be known as the Boston Massacre. They were: Crispus Attucks, a black man with an American Indian heritage, Samuel Gray, Patrick Carr, James Caldwell and my distant cousin, Samuel Augustus Maverick. They are buried in a common grave about four feet from the grave of Samuel Adams.

A protest meeting was held by the colonists at the Old South Meeting House, where one orator proclaimed that every March 5, in that very same meeting place, "discontented ghosts with hollow groans appear to solemnize the anniversary of the Fifth of March."

By pure accident I was in the Old South Meeting House, March 5, 1984, to be with the "discontented ghosts with hollow groans." You may not believe it, but my cousin Sam Maverick began talking to me. This is the exchange we had:

"Cousin Maury, I see that you visited our single grave next to the grave of Samuel Adams, the 'great agitator' who led this nation at Boston into revolution. It is an unusual burial ground. To the rear of us is the grave of Paul Revere. Beyond that are the graves of the parents of Benjamin Franklin. Nearby is the grave of the woman who wrote the famous Mother Goose rhymes."

"What happened that day you were killed, Sam?"

"I was only seventeen years old and an apprentice carpenter. About 150 of us young people were gathered before the Custom House. Samuel Adams called us 'Sons of Liberty' and stirred us up to make trouble. A solitary Redcoat sentry—we called them Lobsterbacks—was walking his post. There were taunts. Crispus Attucks threatened the sentry with a stick. A nineteen-year-old bookseller, Henry Knox, who was later chief of Washington's artillery and our first secretary of war, warned the Lobsterback not to fire his rifle."

"What happened next?"

"The sentry shouted, 'Turn out the main guard.' And with that, officer-of-the-day Captain Thomas Preston came running at us with nine soldiers. We were a mob by then, swinging clubs, throwing pieces of ice. It was then the British killed us."

"What about the funeral, Cousin Sam?"

"We were killed on March 5th, and the funeral was on the eighth. It was a propaganda bird nest on the ground for Samuel Adams, who, with Paul Revere's drawings, turned Boston into a city of manifest frenzy. All shops were closed and the bells of the community were tolled. Our bodies were taken to the very spot we were shot. Five hearses came for us and we were brought to the middle burial grounds and all put in a single grave. That day, though the British issued a proclamation saying we were street ruffians, Samuel Adams scattered about Boston shouting patriotic verses that stirred the colonists up even more."

"What about Samuel Adams?"

"Adams lived from 1722 to 1803 and was considered a failure in life as a businessman and a lawyer. His cousin, John Adams, who later defended the Lobsterbacks who shot us, was embarrassed on occasion by Sam, but Samuel Adams was a profound force for liberty and revolution.... The British governor called him the 'greatest incendiary in the empire.' That was the equivalent of calling him a 'terrorist' in those days. The word 'incendiary' caused the otherwise sensible Englishmen in London to quit thinking, just as the word 'terrorist' causes you living Americans to be dumb about the current world revolution."

"What do you mean by that?"

"The British perceived me to be a terrorist. I hope my more than 250 blood relatives in San Antonio understand that, according to British history, they have a terrorist for an ancestor."

"Why, Sam, the other night at a family party I bragged on you, and one of my relatives said you were 'a nice young English gentleman.'"

"No, that's not so. I was a revolutionary, a man of violence. ...Cousin Maury, you have to accept the truth: you come from people who were called 'terrorists' during the days of the American Revolution."

"Sam, you are asking me to pay too great a price in agreeing I come from terrorists. Why, today all over America, the newspapers, television stations and especially the [slippery] editorial writers put down contemporary revolutions about the world by using the word 'terrorist' as a kind of buzz word to keep the rank and file from thinking. My God, man, I love my cousins, but... I'll get run out of town if I admit you were a terrorist."

"Maury, be serious. In all of history people have been called terrorists. Take the Texas Revolution when the Mexicans called Stephen F. Austin a terrorist and thought they could put down a great revolution with arms. Do you know what Austin wrote in regard to the Mexican government?"

"No."

"Austin wrote, 'I have informed you many times and I inform you again it is impossible to rule Texas by a military system.... Upon this subject of despotism I have never hesitated to express my own opinion, for I consider [military violence] the source of all revolutions and of the slavery and ruin of free peoples.'"

"What's the point?"

"Maury, the point is that neither the Russians nor we Americans are going to put down the world revolution forever. And get this in your head: It isn't a question of communism or capitalism nearly as much as it is a question of nationalism. For God's sake, Cousin Maury, memorize the words of Stephen F. Austin regarding your own Texas Revolution. You living Americans are not going to win in revolutionary situations with military might...."

"Sam, that is some history lesson. And, yes, you were a terrorist, and I'm proud to proclaim that."

"Maury, we are running out of time. You tell my Texas relatives hello, and tell the people to have confidence in the spirit of the American Revolution. Let the light of American liberty inspire the world."

"Good-bye, Cousin Sam."

"Good-bye, Cousin Maury."

With that I began walking out of the Old South Meeting House. As I made it to the door, once again, I heard the "hollow groans of discontented ghosts."

Postscript: There is no exaggeration in today's column. It is a true story, word for word, so help me.

April 8, 1984

The Magna Charta

Johannes Dei Gratia Anglie dominus Hibernie dux Normannie et Aquitannie et comes Andegavie achiepiscopis, episcopis abbatibus comitibus baronibus justicariis, forestariis vicecomitibus prepositis, ministris et omnibus bellivis et fielibus sus salutem.

So begins the Magna Charta, originally written in Latin and translated: "John by the grace of God, king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy, and Aquitane, and count of Anjou, to the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, justices, foresters, sheriffs, stewards, servants, and to all his bailiffs and liege subjects greetings. . . ."

Four original sealed copies of the Magna Charta are in existence. . . .

When it comes to liberty—we the people, we whites, blacks, browns, all races, all creeds—in serious degree owe our liberty to the Magna Charta.

In the beginning it was not a document for the ordinary people. The barons of Runnymede and members of the clergy wrested those words of liberty from King John for themselves, and only for themselves.

They were the rising classes, the new rich, the Johnnies-come-lately who were moving into power. Actually, the Magna Charta was not generally known by the plain people until 1750, when Blackstone printed it in his book The Great Charter and the Charter of the Forest. But liberty is contagious, and little by little from 1215 on the scholars, researchers, monks, dissenters, and other "strange people" became acquainted with the revolutionary idea that a king must answer to the people.

Centuries later it gave people like Patrick Henry ideas. Consider these words of Will and Ariel Durant in their book, Rosseau and Revolution, Simon & Schuster, 1967: "England decided to tax the colonies. In March 1765, Greenville proposed to Parliament that all colonial legal documents, all bills, diplomas, playing cards, bonds, deeds, mortgages, insurance policies, and newspapers be required to bear a stamp for which a fee would have to be paid to the British government."

Patrick Henry in Virginia and Samuel Adams in Massachusetts advised rejection of the tax on the ground that by tradition Englishmen could justly be taxed only with their consent or the consent of their authorized representatives. How, then, could English colonials be taxed by a parliament in which they had no representation? The barons asked that question for themselves in 1215.

Years ago my father wrote a book on constitutional liberty called In Blood and Ink, Starling Press, 1939.

His analysis of the Magna Charta was considered controversial at the time, 1939, and is here quoted in part: "In our high school and college history books we see pictures of King John properly robed in brilliant colors, surrounded by a brilliant assemblage of the nobility, dejectedly, yet magnificently, signing the Magna Charta. . . . But the facts are he did not sign it, that he was a plain-looking drably dressed fellow, and that the barons who forced him to agree were a lot of selfish men who, on their way to Runnymede, had stopped in London long enough to slaughter and pillage the Jews. . . . It was at the time a reactionary instrument, a sort of private treaty between the king and the nobles and the higher clergy. Most of the modern authorities on Magna Charta do not regard it as having had any constitutional worth at the time it was written. But Professor William McKechnie of Glasgow, in his great work, Magna Charta, says: 'The greatness of Magna Charta lies not so much in what it was to the framers of 1215, as in what it afterward became to the political leaders, judges, and lawyers, and to the entire mass of men of England in later ages.' After all, the charter did represent the will of more people than did the decrees of one selfish king; in that sense it was an extension of economic and political liberty. Thus Magna Charta gradually grew in the minds of the people as the Great Charter of Liberty. It has proved through our history a sort of spiritual shield of liberty, the original protector of habeas corpus, trial by jury, due protection by the court of the individual, and all those other rights that make for human decency, dignity, self-respect, and free government. Magna Charta—in 1215—was not a people's charter. It changed their miserable lot not one iota. But it did set forth for English-speaking people certain rights and liberties that all men desire and that many have since won. It is the first of a series of documents marking the people's long uphill battle for their freedom."

Actually some words in the Great Charter are quite inspiring. For example, Section 39: "No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised [dispossessed] or exiled, or in any way destroyed nor will we go upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land.

Of course, the barons and the clergymen meant that they were the ones to whom those rights should be afforded. But liberty, as I said, is contagious, and little by little, century after century, the plains people found out about Magna Charta and said: "We want this liberty, too."

Magna Charta gave people ideas. It helped John Locke to formulate the concept that man is born with certain natural rights. The late Robert Hutchins used to talk about the people of one time and era talking to people of another time and era.

In this sense, the barons of Runnymede talked to Locke, who talked to Blackstone, who talked to Jefferson, who talks to you and me. As we fight our way past "the cross, the stake, and the hangman's noose," to use a phrase of Hugo Black's, the Magna Charta remains an incredibly important milestone. Maybe the most important.

The dreadful thing about all this is that we contemporary folks run out on our documents of liberty. Just as King John tried to repudiate the Magna Charta, and as the newly powerful of 1215 insisted it was only for themselves, we Americans ran out on the concept of the Bill of Rights when we tolerated the passage of the Alien and Sedition Laws [of the 1790s].

We ran out on the Fourteenth Amendment when it came to the blacks. Free speech is okay as long as you are not a Red or a Ku Kluxer. State judges have totally ignored the Bill of Rights of the Texas Constitution, almost as if it had never been written.

During the Joe McCarthy days I was a member of the Texas House of Representatives and got a taste of all this. Attempts were made to intimidate schoolteachers, effort after effort was made to censor books, an Un-American Activities Committee was recommended to the legislature by the American Legion. In the middle of one such hot, unfriendly, and intemperate debate, I quietly read the following statement to the entire House: "All political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority, and instituted for their benefit. The faith of the people of Texas stands pledged to the preservation of a republican form of government and subject to this limitation only, they have at all times the inalienable right to alter, reform, or abolish their government in such manner as they think expedient."

As soon as I left the podium, one legislator demanded of the speaker he be permitted to address the House on personal privilege. That is supposed to be a moment of great honor, great outrage, and when a member says those powerful words "personal privilege" a great hush ordinarily comes over the legislative body. So it was after I had spoken the above words. It was a scary and spooky moment.

My colleague told the House I had spoken "seditious words" and that I owed the members "an apology."

"Where did the gentleman from Bexar get that language?" it was asked. I finally told my brother legislators: "I got it from the present Constitution of the state of Texas." Word for word, and it was language at least distantly rooted in the Magna Charta. . . .

April 6, 1980

America Loses By Ignoring Indian Heritage

Most Mexican-Americans of Indian descent do not know who they are. Stop any ten such persons and ask: "What do you know about your Indian ancestry?" You will get a blank stare nine times....

Why this lack of knowledge?

There are all kinds of unhappy reasons for this, "thanks" significantly to the Spanish—secular and religious—and later to us gringos. It is the kind of demeaning thing that caused Porfirio Diaz, the mostly Indian former president of Mexico, to send off to Paris for a cream that, he thought, would lighten the color of his skin. It is reflected in all the school systems of Bexar County by the lack of textbooks or courses which adequately tell students about the people of Indian heritage.

The school authorities of Maine have come out with a textbook that I think is one of the most exciting books I have ever read: Maine Dirigo, I Lead, produced by Maine Studies Curriculum Project, Down East Books, Camden, Maine. I found out about it from the Quakers.

The chapter on Indian history begins with an Indian by the name of 'Moomoom' who tells the junior high school students of Maine about himself and his people. Let's pretend we are sitting around a campfire. Brothers and sisters, you be quiet now, you hear me? Listen to the old man talk: "I am Moomoom of the Penobscot Nation. 'Moomoon' in my language is a nickname for "grandfather."...I have seen many changes in my lifetime, but only one thing hurts me very much. It is the way many people still 'see' me and my people. This story I have to tell is a painful one for me. It is true that nearly everything written about my people has been written by non-Indians. When Europeans first came to the area now known as Maine, they wanted our land, and they even fought to take it away from my people. What they wrote about us was not always true. Some things were lies. Others were just misunderstandings. To begin, let me say that many Native Americans do not like the name that Columbus gave us. We are not really Indians and this is not India. We are Sioux or Seminole or Wabanaki.... One thing that history books often say is that the Europeans 'discovered' the Americas. I must tell you that it was my people who discovered this land.... By the time Columbus stumbled on the West Indies, there were at least fifteen to twenty million native people in North and South America...."

Our Indian friend Moomoom then criticizes the use of the term 'prehistory." Once again, let's listen to the Indian grandfather: "Another thing we do not like is the way a part of our history is called 'prehistory' just because it happened before Europeans came here. In our view, everything that has happened to us is part of our history. Our history was not written; it was oral history passed down by word of mouth.... Unfortunately "prehistory" is an English word which means that part of history which happened before there was anyone who could write it down or record it.... From our point of view, however, this word "prehistory" seems to say that our legends and oral histories of what happened before the Europeans came here are not history.... When explorers arrived here, they did not understand us. What they said about us showed only the European point of view and not our point of view. Since everything written about us was written by Europeans, nearly everything said about us was biased from the European point of view. "Bias" is an important word for you to know when you study history. It means seeing events from only one point of view and forming an opinion before looking at all of the facts.... As an excuse for what they were doing, most Europeans said their people were better than ours. Many called us 'savages....' Puritans in Massachusetts, especially, said we were 'children of the Devil.' Seeing us in those biased ways made it seem right for them to treat us badly. Indeed, most Europeans had the same opinions of native people in South America, Mexico, and elsewhere...."

We folks of European descent have devastated the land and nature, and Moomoon doesn't think much of that. He went on: "Until the Europeans came here, we depended on the land for everything.... We could not afford to damage [the land] as the Europeans often did.... In the early spring, we moved to the hills to tap the maples for their sweet sap. Later we moved down to the streams...to catch fish.... To us, the whole nature was sacred. Our survival depended on the survival of everything else. In fact, we thought of animals as our relatives.... We did not kill young animals and took only what we needed. We gave thanks to the spirit of every animal and plant we needed to kill for our use."

And on the subject of religion, Moomoom has his doubts about Christianity: "Most early writers could not see the spiritual side of our lives. When they saw some of our spiritual practices, they called us...'pagan,' just because we were not Christian. Because we saw everything as sacred, the Europeans thought we worshipped many gods. In fact, we recognize only one force of good in the world: the Creator or the Great Spirit. When missionaries tried to convert us, they felt they had to tell us that our Great Spirit was the Devil."

Finally, Moomoom has some thoughts about land ownership: "Perhaps the most important area of misunderstanding between our culture and that of the Europeans was in our different understanding of what it means to own land.... We could no more sell land than we could sell the water or the air.... Kings and queens made people believe they own land.... It was [kings and queens] who often granted territory...without considering our aboriginal rights...."

Well, the campfire is low, and it is time to bid Moomoom good-bye. I thank him for his thoughts and thank the folks who wrote the magnificent book Maine Dirigo, I Lead.

To the people of Mexican descent with Indian heritage, let me close out today's column with a question: Why don't you know more about your Indian ancestry? You need to know about it, and so do we gringos. If we did, we might have a better understanding of the family of man.

In peace, friendship, and respect.

May 2, 1982

Nazis Murdered Millions of Non-Jews

I was repelled by the conglomeration of races, repelled by this whole mixture of Czechs, Poles, Hungarians, Ukrainians, Serbs, and . . .Jews. . . .Adolph Hitler, Mein Kampf

The conclusions here are totally my own, although I must thank Paula Kaufman, a member of San Antonio’s Temple Beth El, for providing me with a hefty part of the research of which this particular column is based. I found her a cheerful working person.

I had gone to the synagogue for background information after reading the July 15, 1979, story by Michael Getler of the Washington Post entitled, “The Man Who Stalks the Nazis.” It was about Simon Weisenthal, who spent nearly five years in a Nazi concentration camp at Mauthausen, Austria, and who is more famous for his capture of Adolph Eichmann.

Getler quoted Weisenthal at length, but the remarks attributed to him that especially caught my attention were these: “I am not dividing the victims. This was one of the biggest mistakes made on the side of the Jews. Since 1948, I have fought with Jewish leaders not to talk about six million Jewish dead but rather eleven million civilians, including six million Jews. This is our fault that in world opinion we reduced the problem to one between Nazis and Jews. Because of this we lost many friends who suffered with us, whose families share common graves. After the war, there was a possibility to make a brotherhood of victims and survivors against dictatorship. But the survivors were sometimes misrepresented after the war by people sitting in safe countries during the war. . . .”

Who were the non-Jews—some say as many as nine million—murdered by the Nazis? Who gives a hoot in hell in our country? For the most part, American Jews have been just about the only ones in America who have cared enough at least to do research on gentile civilians killed by Hitler. Virtually no one else has done this research and least of all have American gentiles done anything about it from a standpoint of scholarly research. Isn’t this rather astonishing?

For two years I went from library to library trying to find out the truth. Through U.S. Senator John Tower’s office I enlisted the help of the Library of Congress, one of the greatest libraries in the world. The research it sent back to Tower wasn’t worth a bucket of warm spit. How in the name of God could four to nine non-Jewish helpless human beings be systematically put to death and we know so little?

I suspect our own Jim Crow notions have something to do with the lack of concern. Most of the dead were Easter European Roman Catholics. Others were Marxists, labor leaders, iconoclasts, and gypsies. More specifically they evidently were:

-One million Polish civilians, including seven Roman Catholic priests killed not too long after Poland was invaded.

-Two million Soviet prisoners of war. All unarmed.

-One million Soviet citizens and Slavs.

-Two hundred thousand gypsies, mostly the ones used for medical experiments by German medical doctors who didn’t bat an eye, plus retarded people.

-Several hundred Spaniards hiding out in France¬—men who had fought Franco.

-One hundred seventy disarmed British soldiers near Dunkerque, and later seventy unarmed Canadian soldiers near Caen, France.

-Thirty-two thousand German civilians killed for “political crimes” including communists, writers, labor leaders, teachers, pacifists, and homosexuals.

The other night, I went to a memorial service at Temple Beth El for the Holocaust Jewish dead. It was a heart-wrenching experience watching twelve Jewish survivors walk down the middle aisle to the strains of a violin.

But there was something missing that evening. The words of Simon Weisenthal came back to me.

Why separate the family of man when it comes to helpless human beings murdered by the Nazis? Christians had been invited to attend, but only a few Roman Catholics and a Lutheran preacher plus half a dozen other gentiles were there. Why not next time have a cross section of the community present and all victims of the Holocaust be remembered? We good Christians did the killing, and most of all we are the ones who need to be there.

One way to remember what went on at those camps were Jews and non-Jews were murdered is to buy the phonograph record, “Songs from the Depths of Hell,” by Alexander Kullsiewicz, a Folkways album. A young clockmaker from Bilgoraj, Poland, was forced to watch as his wife was taken into a crematorium at Treblinka. Then he saw his three-year-old son’s brains bashed out. The father, a musician, that night wrote a song about it and actually sang it in some kind of a strange hope it might bring his child back to life. This song and others were sung to Kullsiewicz, also a concentration camp inmate, who gathered them together and made them into the album. They are, indeed, songs from the depths of hell.

Can it happen again? Maybe . . . [if we forget the statement attributed after World War II to] pastor Martin Niemoller: “First the Nazis came for the communists; and I didn’t speak up because I was not a communist. Then they came for the Jews, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a Jew. When they came for the trade unionists I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a trade unionist. And when they came for the Catholics I didn’t speak up because I was a Protestant. Then they came for me . . . and by that time there was no one left to speak up for me.”

May 17, 1981

Newton Boys Were Gentle BanditsThe most successful bank and train robbers in American history, the Newton Boys (of Uvalde) still have not made it into the pantheon of famous outlaws, despite their having robbed more than sixty banks and six trains in four years . . . their career culminated with the biggest train robbery in U. S. history at Rondout, Illinois, on June 12, 1924. By their own accounting, they made out with more loot in those four years than Jesse and Frank James, the Dalton Boys, Butch Cassidy, and all other famous outlaw gangs put together.

I wanted something . . . and I knew I would never get it following a mule's ass and dragging cotton sacks down them middles.Willie Newton, The Newton Boys, by Claude Stanush and

David Middleton, State House Press, 1994.

The thing that most attracted [Claude Stanush to] the Newton brothers—Willis, Jess, Doc and Joe . . . was their claim that in all their robberies, they never killed anyone.

Willis told Stanush: "We wasn't gunfighters, and we wasn't thugs like Bonnie and Clyde. All we wanted was the money. We was just businessmen like doctors and lawyers and storekeepers. Robbin' banks and trains was our business. . . . When we went on a job I told the boys, 'If you have to shoot, don't shoot to kill.' In fact, we loaded our guns with bird shot a lot of times to make sure we didn't kill nobody. We never did."

Those distinguished Newton capitalists, who stole less than savings and loan officials and bankers during the last ten years, spent a fair amount of time in various prisons about the country.

The most innovative of the Newton brothers during their convict days was Willis, who pulled off the slickest trick in the history of Huntsville. He wrote the judge and sheriff who had a lot to do with sending him to the penitentiary and asked that they join in a request for [his] pardon. They both wrote back saying they would not help.

Willis then forged their signatures to a pardon application and had about sixty of his buddy convicts sign the application as if they were upstanding citizens. The warden told Willis it was the finest pardon application he had ever seen, and with that Governor William Hobby granted Willis his pardon. . . .

The Newton Boys includes a fourteen-page prologue and an eight-page epilogue that Stanush and Middleton wrote together. The rest consists of conversations, mostly with Willis, which begin at page one with this comment: "I'm Willis Newton, and I live in Uvalde, Texas. I was born in Callahan County near the town of Cottonwood southwest of Dallas, January 19, 1889. . . . In my time I robbed over eighty banks and six trains. On most of these jobs Jess, Doc, and Joe was with me . . . we was just quiet businessmen."

Now and then there is an editor's note, such as this one at page 267: "The Newtons' successful career as robbers came dramatically to a climax on the night of January 12, 1924. The four of them . . . held up the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul mail train . . . about twenty-five miles northwest of Chicago. . . . Approximately $3 million was seized, making this, in the words of the

Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1924, 'the biggest of all mail robberies.' That's when they went to Leavenworth."

Folks in Uvalde remember the Newton Boys in a good-natured way. I called former Governor Dolph Briscoe. . . . I asked Dolph: "Is it true the Newton Boys never robbed your Uvalde bank because that's where they kept their money?" Dolph laughed at that, but would neither affirm nor deny the rumor. He did say: "The brothers borrowed money from us and always paid it back on time. Their word was good at First State Bank in Uvalde."

I mentioned U. S. District Judge Darwin Suttle to Dolph, who told me: "Judge Suttle when practicing law in Uvalde was one of the finest and most able lawyers I ever knew. He represented John Garner and he represented First State Bank."

Suttle explained: "I slightly knew the Newton Boys, but the one who was my friend was Joe, who sold me the best horse I ever had. Joe was always completely honest with me." Margaret Rambie, in a

Uvalde News Leader column, described Joe as "my favorite bank robber."

February 27, 1994

Critics Can't Dim Alamo Symbolism

In the summer of 1960 I received a letter from Jack Fischer, then the editor of Harper's magazine, asking that Walter Lord be shown around because he was coming to Texas to do a book on the Alamo.

Fischer grew up on a farm across which, he claimed, the boundary lines of Texas and Oklahoma ran. Successor to Bernard De Voto in writing a historically famous column, "The Easy Chair," Jack was a one-time working newspaper reporter, an immensely decent editor who loved our country in a way no yahoo could understand. I was glad to accommodate him.

Walter Lord turned out to be a delight. Bright, friendly, and the first to laugh at himself, he quickly won the approval of the good sisters at the Alamo library.

We left for Goliad on a fact-finding expedition. A hundred and twenty some odd years earlier, Travis had asked Fannin to join him in San Antonio. What was the extent of communication between the two? We discovered a thing or two about that, but as an interesting sidelight we came upon a nugget of history, the original journal of Dr. Joseph H. Barnard, the surgeon who was spared at the Goliad massacre.

In the journal there was this remedy by the doctor for curing colds: "Tincture of Cannabis India, three ounces...."

When his book, A Time to Stand, was finally published, Walter raised some questions about the Alamo. Did Travis really draw a line? (There is no concrete proof that he did.) Did Travis wear the fancy uniform artists put him in? (No.) Did David Crockett surrender? ("It's just possible that he did.") How many Mexican casualties? ("Best estimate seems about six hundred killed and wounded.") What flag did the Texans fly? ("Probably the azure flag of the New Orleans Greys.")

What's the truth generally about the Alamo? Were there any warts? Yes.

The battle was fought in direct violation of General Sam Houston's orders to abandon the place. Like a wildcat strike, it was a wildcat battle.

While the defenders spoke of liberty for themselves, they were perpetuating the institution of slavery. After the battle was over, the black slaves in the Alamo were spared by Santa Anna. One slave named John chose to fight alongside the Texans; he was put to death. History does not even do John the dignity of giving him a last name.

G. J. Sutton, the late black legislator, used to rawhide me about the Alamo and slavery. In between denouncing my ancestors, he would call John the dumbest black in history for fighting with the Anglo-Texans. Even if they had won, John would have remained a slave, Sutton said, glaring at me all the time....

April 22, 1979

Remember the 'Real' Alamo

My old pal, Gus Garcia, may his soul rest in peace, invited me to be the only Anglo lawyer in the United States to be co-counsel on the U. S. Supreme Court case that declared unconstitutional the exclusion of Mexican-Americans from the right to serve on juries.

That was when Gus stood before the High Court and referred to Sam Houston as "that wetback from Tennessee" and made the judges laugh....

Gus Garcia was wrong in contending that Mexican-Americans should have no interest in the Alamo. Anglo historians are entitled to an even harder rap on the knuckles for they, along with Gus, have ignored the "Tejanos" or Mexicans who died at the Alamo....

The cat, therefore is about to slip out of the bag about the "Tejanos"—the Texas-Mexicans at the Alamo who had strong ideas about liberty, completely distinct from the likes of the hated Santa Anna to the south and the encroaching Anglos from the north, one of whom was my great-grandfather, Sam Maverick, who was elected by the defenders of the Alamo to sign the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Texas. (It was the luckiest election any Maverick ever won in San Antonio.)

But Anglos, forgetting the Tejanos, have used the Alamo as a racist symbol. John Wayne's movie, The Alamo, had a then-record budget, but the script had some of the worst mistakes in the history of Hollywood. The actors referred to the Rio Bravo (an old name for the lower part of the Rio Grande) as the river running near the Alamo. In one scene Colonel Travis explains to his fellow defenders that the Alamo is north of the Sabine, which is strange because the Sabine is the boundary between Texas and Louisiana. In another scene, Fannin is said to be marching south to San Antonio from Goliad. Every time I have ever gone to Goliad it has been the other way around....

Professor Don Graham gives all Texans, Anglo and Mexican-American, some good advice with these words: "What the Alamo story needs more than anything else is the application of critical intelligence to its traditions, legends, and stock images. And that, of course, is what it has least often had. Confronted directly, the Alamo story seems to make the eyes glaze. The heroes take on the smooth patine of public statuary seen from a distance. In fiction or film such pageant-like figures are deadly...."

There is a play about the Alamo by the late Ramsey Yelvington called A Cloud of Witnesses. In technique it draws from the Greek theater, the morality play of the Middle Ages, the Japanese, and from the ballad singer.

At the conclusion Satan suddenly appears in a puff of smoke, the fires of hell swirling around him. He mocks the dead defenders, who by then are standing at the front of the stage with the women of Gonzales humming their song of death in the background. A dialogue develops with the Devil. The Alamo defenders, Abamillo, Badillo, Espalier, Esparza, Fuentes, Guerrero, Losoya, and Nava, have their say along with the rest.

Then in one voice the slain Texans, Anglo and Mexican, speak their final words, "Only this we know: We died there, and from our dust the mammoth thing freedom received a forward thrust. The reverberations we continued are something to which man may respond or not respond, at pleasure."

Well, there is an excess of nonsense written about the Alamo. How can anyone write with total objectivity on such an explosive subject? Worse still, too often the Alamo is presented in a way that makes it a jingoistic insult to present-day Mexican-Americans....

Now and then I walk through the Alamo grounds. It's a good place to think about our country, for courage is courage whether it is a Cleto Rodriguez in World War II or blacks dying out of proportion to their numbers in Vietnam. Or, yes, the blue-eyed ones, who, legend has it, first listened in the dark of the night to the battle of John McGregor's bagpipe versus the fiddle of former Congressman Davy Crockett and then died hard.

The Alamo is a controversial, even sore, subject in this city, but even its critics have taught me some things—black people like G. J. Sutton and hell-raising Mexican-American intellectuals like the late Gus Garcia. And there have been old Anglo friends and relatives, poems, books, plays, Walter Lord, and wonderful librarians who have all combined to give me an expanded view. What we see with our mind's eye is more important than with the physical eye.

In that sense, warts and all, I care deeply about the old Alamo.

December 29, 1985

Japanese-TexansEighteen thousand individual decorations for valor including one Congressional Medal of Honor, fifty-two Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service medal, 560 Silver Stars and twenty-eight Oak Leaf Clusters, twenty-two Legions of Merit, fifteen Soldiers' Medals, four thousand Bronze Stars and twelve hundred Oak Leaf Clusters, twelve French Croix Guerre, two Italian Medals of Valor, 9,500 Purple Hearts and Oak Leaf Clusters. As a unit: forty-three Division Commendations, two Meritorious Service Unit Plaques, and seven Presidential Distinguished Unit Citations.Awards of the men and of the 442nd (Japanese-American) Combat Team,

the most highly decorated military unit of its size of all U.S. combat outfits

in World War II; from the book Nisei: The Quiet Americans,

Morrow, 1969, by Bill Hosokawa.

The truth was that not one living person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States or Territories of Alaska and Hawaii was ever charged with, or convicted of, espionage or sabotage.From the booklet, The Japanese-American Incarceration

published by the Japanese American Citizen League.

Have you ever driven down a highway with a fellow native-born American who was in an American concentration camp? Well, I did a few days ago with [Japanese-American] Alan Y. Taniguchi, former dean of the School of Architecture, University of Texas, and . . . a highly regarded Austin architect in private practice. We were on our way to Crystal City, where Alan's father, Isamu, mother, Sadayo, and brother, Izumi, had been interned [during World War II]. Alan, an adult at the time and separated from his family, was in an Arizona camp. "The first one in our family to be picked up," Alan began telling me, "was my father in January of 1942. I was studying architecture at the University of California at Berkeley when I got a call to come home immediately. We had a farm near Brentwood in northern California. My mother had set the table for lunch in the Japanese style with chopsticks. A sheriff, his deputy, and an FBI agent were there. The deputy said he had come to America from Ireland when he was six, but upon observing the chopsticks remarked, 'You people never will be Americans.' I said back to him, 'Do you still eat Irish potatoes?' He pulled a pistol from his belt and pointed it at me. The FBI agent knocked the pistol out of the deputy's hand and told him to be courteous. To this day I appreciate the decency of that FBI agent. Then they carried my father away, and I was not to see him for around three years."

In the back of our car as we drove to Crystal City was a model of the monument that Taniguchi has designed and that is where the Japanese were interned.

"Alan," I asked him, "are you still bitter?"

There was a pause. "I don't know my wife, Leslie, says I am because I won't stop talking about the concentration camps. . . . suppose we went to war with Mexico. What would happen to Mexican-Americans in San Antonio?" Taniguchi asked.

"Well," I answered, "San Antonio has a huge Mexican American population."

Once we made it to Crystal City, we were met by various local officials and citizens who could not have been more courteous at the official ceremony when the model was presented. One speaker said the concentration camp site was a place of sorrow not only for the Taniguchis but for others as well. Before the Japanese were there, it had been a temporary home during the New Deal for migratory workers. They rested there before following the crops north under sorry conditions.

After the Japanese left, it became a segregated Jim Crow school for Mexican-Americans.

On the way back to San Antonio, Taniguchi handed me the book,

Years of Infamy, Morrow, 1976, written by his cousin, Michi Weglyn. He asked me to read the introduction by James Michener. Husband to a woman of Japanese descent, Michener wrote: "[W]hen Tom Clark resigned from the Supreme Court in 1966 he did purge his conscience, confessing that while attorney general of the United States he shared the national guilt regarding the Japanese-American internments. 'I have made a lot of mistakes in my life. . . . One is my part in the evacuation of the Japanese from California. . . . Although I argued the case, I am amazed the Supreme Court ever approved it.'"

But Michener had more to write. "And the stoic heroism with which the impounded Japanese-Americans behaved after their lives had been torn asunder and their property stolen from them must always remain a miracle of American history. The majesty of character they displayed then and the freedom from malice they exhibit now should make us all humble."

"Maury," Taniguchi suddenly asked me as we got near San Antonio, "do you know how I got the first name of Alan?"

"No."

"My first name at birth was Yamamoto. Well, it was decided I wasn't a security risk and that I could get out of the camp while the war was still going on. At that time the Japanese battleship Yamamoto was prowling the seas, and so my buddies in the camp said: 'You need a new first name.' That's how I got the name Alan."

Alan Yamamoto Taniguchi is an easy fellow to be around, laughing at himself, smiling often, and full of hope for a better America. He could not, as an aside, be more proud of his father who designed the incredibly beautiful Zilker Gardens in Austin, just beyond Barton Springs.

My friendship with this Japanese-American has forced me to study and understand for the first time some unhappy history: the real drive against people of Japanese descent in our civilian government at the time came from liberals-liberals who ran out on their principles. The single most important legislative voice supporting procedural due process for the "Japs" came from a staunch Republican conservative: U.S. Senator Robert Taft.

But everything has to come to an end. By then Taniguchi had driven me to my home. "Thank you for going with me to Crystal City. Don't ever forget those concentration camps," he said. We waved good-bye, and I watched him drive away, a good fellow, and a fine American. . . .

[Later], Alan Taniguchi . . . was on the telephone asking me: "Will you give the dedication speech for the concentration camp marker at Crystal City?"

Of course, I would make the speech. After all, the much-respected Jingu family, who used to live at the Japanese Gardens of San Antonio, had taught me over half a century ago about the decency, patriotism, and hard-working qualities of Japanese-Americans. . . .

Grandpa Taniguchi, five feet two inches tall and weighing less than a hundred pounds, died in 1992, but he was everybody's pal in Austin. Not only that, he was the No. 1 hero of the Men's Garden Club with his Japanese vegetables, bonsai trees, and Japanese cherry trees, which he planted all over Austin after grafting Japanese cuttings to the roots for a wild Texas plum.

I enthusiastically point out that the words "concentration camp" are engraved on the historical marker at the site rather than some sweetie-pie euphemism like "evacuation center." A rose is a rose, and a concentration camp by any other name is still a concentration camp.

One person's hero is another person's villain. My hero, Franklin Roosevelt, is a villain to many Japanese-Americans because on February 19, 1942, he signed Executive Order 9066 resulting in the incarceration of the [U.S.] mainland Japanese.

Roosevelt did this at the urging of the professional military but against the advice of his then-attorney general, Francis Biddle, who considered it an immoral act.

Here's a good question: If the people of Japanese ancestry were so "disloyal," why were the Japanese on the Hawaiian Islands, in the very heart of U.S. military operations for the Pacific, permitted to go free?

But one of my heroes is a hero to the Japanese-Americans: Eleanor Roosevelt. I asked Alan Taniguchi if he had any memory of her. "Oh, yes," he replied, "because she came to my concentration camp and walked among us without guards, inquiring as to our well-being. Eleanor Roosevelt is a saint to the people of Japanese ancestry. . . ."

The dedication ceremony would not have been a reality without the help of the people of Crystal City. Former County Judge Angel Gutierrez first proposed the concentration camp marker. Rudy Espinosa, the superintendent of schools, is the person who most consistently worked for the memorial. County Judge Ronald Carr has been a friend, as have various city officials.

Crystal City has had its own local racial tensions but as to the honoring of Japanese-Americans, all groups in that community joined together to do the kind and thoughtful thing. Maybe the marker will be a symbolic flower working its way past economic despair and occasional racial bitterness. A round of cheers for the good folks down there!

There was a table in front of the marker we dedicated, on which was placed a plate of biscuits. After the ceremony was over, the people of Japanese ancestry walked among those present, inviting one and all to break the bread as a symbol of brotherhood and sisterhood. It could not have been a more touching moment.

But the more dignified those Japanese-Americans were at the ceremony, the more I thought about how we Caucasians had done them.